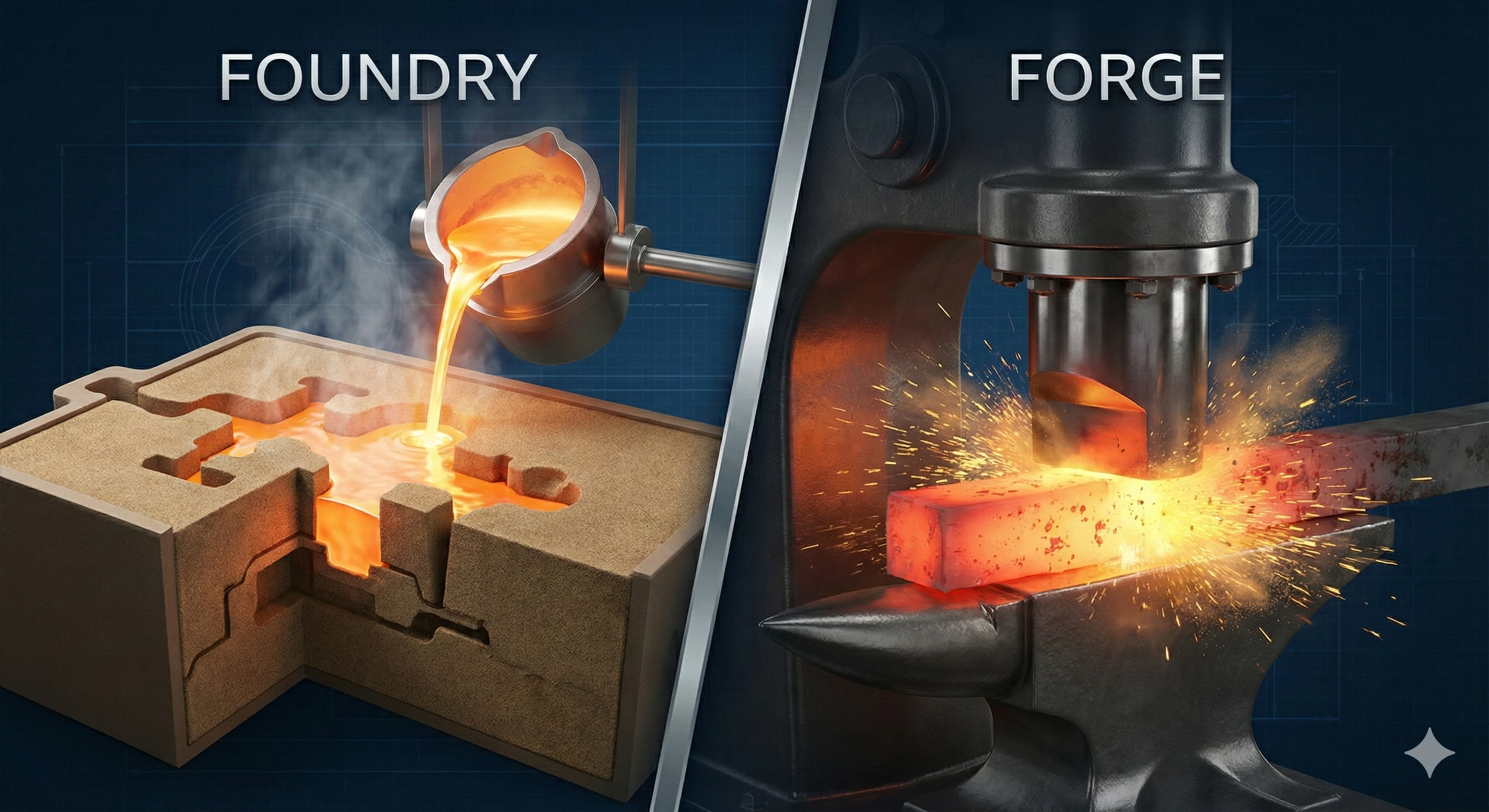

The primary difference lies in the state of the metal during processing. A foundry melts metal into a liquid to pour it into molds for creating complex shapes, whereas a forge heats solid metal to soften it before shaping it with compressive force to maximize structural strength.

To help you make the right decision for your next project, we have broken down the science, the processes, and the pros and cons of each method below.

What is a Foundry? (The Art of Liquid Metal)

In our daily operations, the foundry side of the business deals with extreme heat and fluidity. We start every shift by checking the furnaces where raw stainless steel is melted down completely. It is a process of transformation that relies on chemistry and precise temperature control rather than brute force. We rely on gravity or pressure to fill a void, creating parts that would be impossible to machine from a solid block.

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings by melting metal into a liquid state. This molten material is poured into a mold made of sand, ceramic, or metal, where it cools and solidifies. This process is uniquely capable of creating intricate internal cavities and complex geometries.

To understand what happens in a foundry, think of the "Ice Cube" analogy. If you want to make an ice cube, you melt water into a liquid, pour it into a tray (the mold), and let it freeze (solidify). Casting works exactly the same way, just at much higher temperatures—often exceeding 1600°C for the stainless steel glass hardware we manufacture.

The Process of Investment Casting

At our facility, we specialize in (also known as lost-wax casting). This specific foundry method is favored for precision parts like glass spigots and shower hinges.

-

Pattern Creation: We inject wax into a metal die to create a replica of the final part.

-

Shell Building: This wax is dipped into ceramic slurry multiple times to build a hard shell.

-

Dewaxing: We heat the shell to melt the wax out, leaving a hollow cavity.

-

Pouring: Molten metal is poured into this ceramic shell.

The Superpower: Complexity

The main reason engineers choose a foundry solution is geometric freedom. Because liquid flows, it can go anywhere. If you need a pump impeller with curved internal vanes or a valve body with a hollow chamber, you cannot forge it. You must cast it.

Key Characteristics of Foundry Work

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| State of Matter | Liquid (Phase Change from Solid to Liquid to Solid) |

| Tooling | Molds (Sand, Ceramic shell, or Metal die) |

| Best For | Complex shapes, hollow parts, thin walls, and intricate details. |

| Material Flexibility | Extremely high; almost any metal can be melted and cast. |

What is a Forge? (The Art of Solid Force)

Unlike the pouring decks in our foundry, a forging operation is defined by rhythm and impact. If you walked into a forge, you would feel the ground shake. There is no molten liquid here; instead, there are glowing red and massive hammers. When we look at components that require absolute safety reliability—like the connecting rods in our delivery trucks—we know those parts were born from force, not flow.

A forge is a manufacturing facility that shapes metal while it is in a solid, plastic state using localized compressive forces. By heating a billet until it is soft and malleable, then applying massive pressure with hammers or presses, forging aligns the grain structure for superior strength.

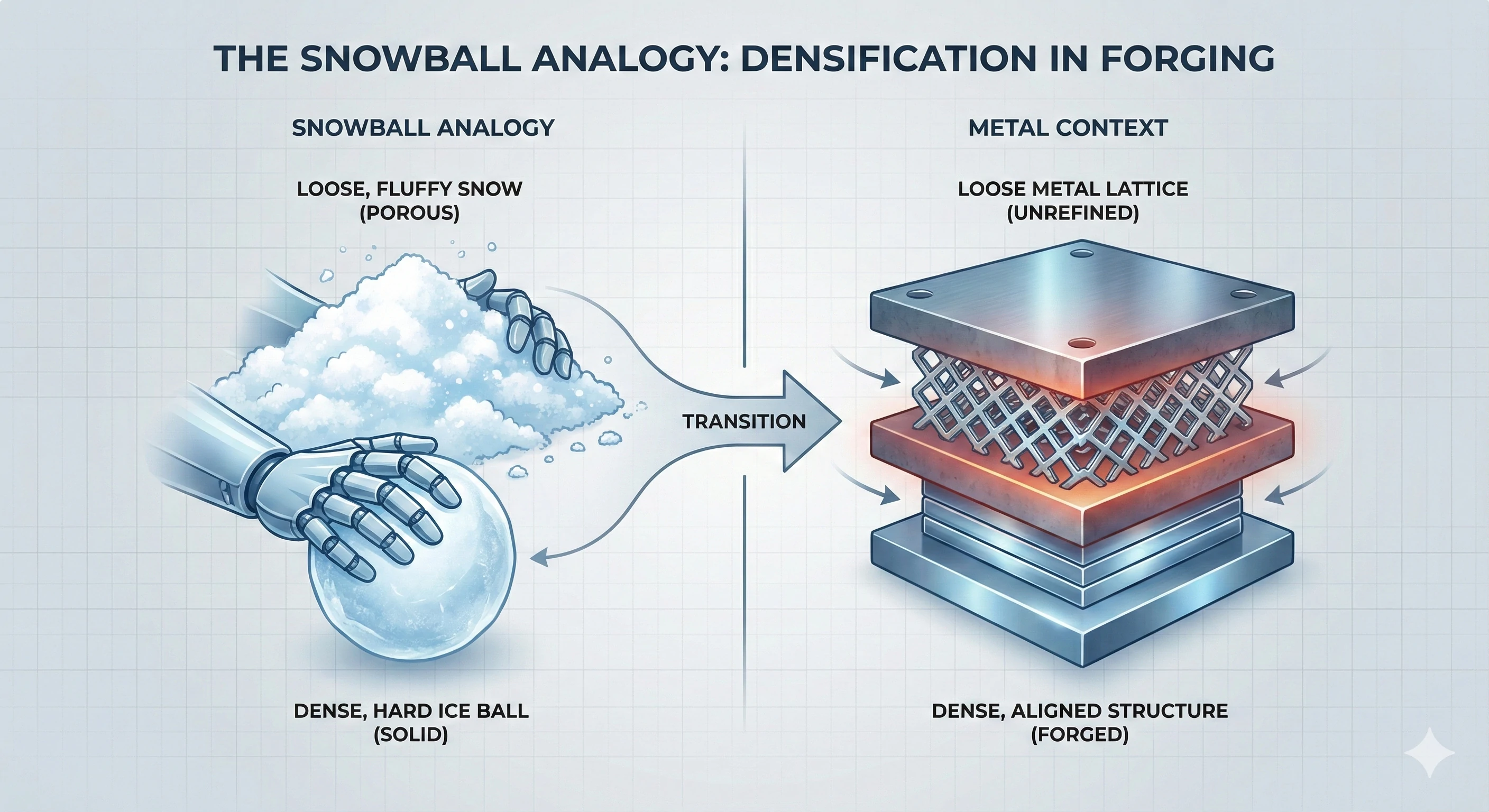

If casting is making an ice cube, forging is making a "Snowball." You take snow (solid material), and you pack it hard with your hands using pressure. You do not melt the snow; you compress it. The more you compress it, the harder and denser it becomes.

How Forging Works

The process typically involves heating a metal slug or billet until it glows red. At this temperature, the metal is plastic—soft enough to shape but still solid. It is then placed between two (the top and bottom molds). A massive hammer drops down, or a press squeezes the metal, forcing it to fill the shape of the die.

The Superpower: Strength

Forging eliminates internal voids. In casting, you might occasionally get (tiny air bubbles) trapped inside the metal if the process isn't controlled perfectly. In forging, the immense pressure squeezes these defects shut. This makes forged parts the standard for safety-critical applications where failure is not an option, such as aircraft landing gear, automotive crankshafts, and high-stress hand tools like wrenches.

Types of Forging Operations

| Type | Description | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Open Die Forging | Metal is hammered between flat dies; the operator moves the piece. | Large shafts, rings, and custom shapes. |

| Closed Die Forging | Metal is forced into a die that contains the specific shape. | Gears, connecting rods, small tools. |

| Roll Forging | Metal is passed between rollers to reduce thickness. | Long parts like axles or leaf springs. |

The "Grain Structure" Battle?

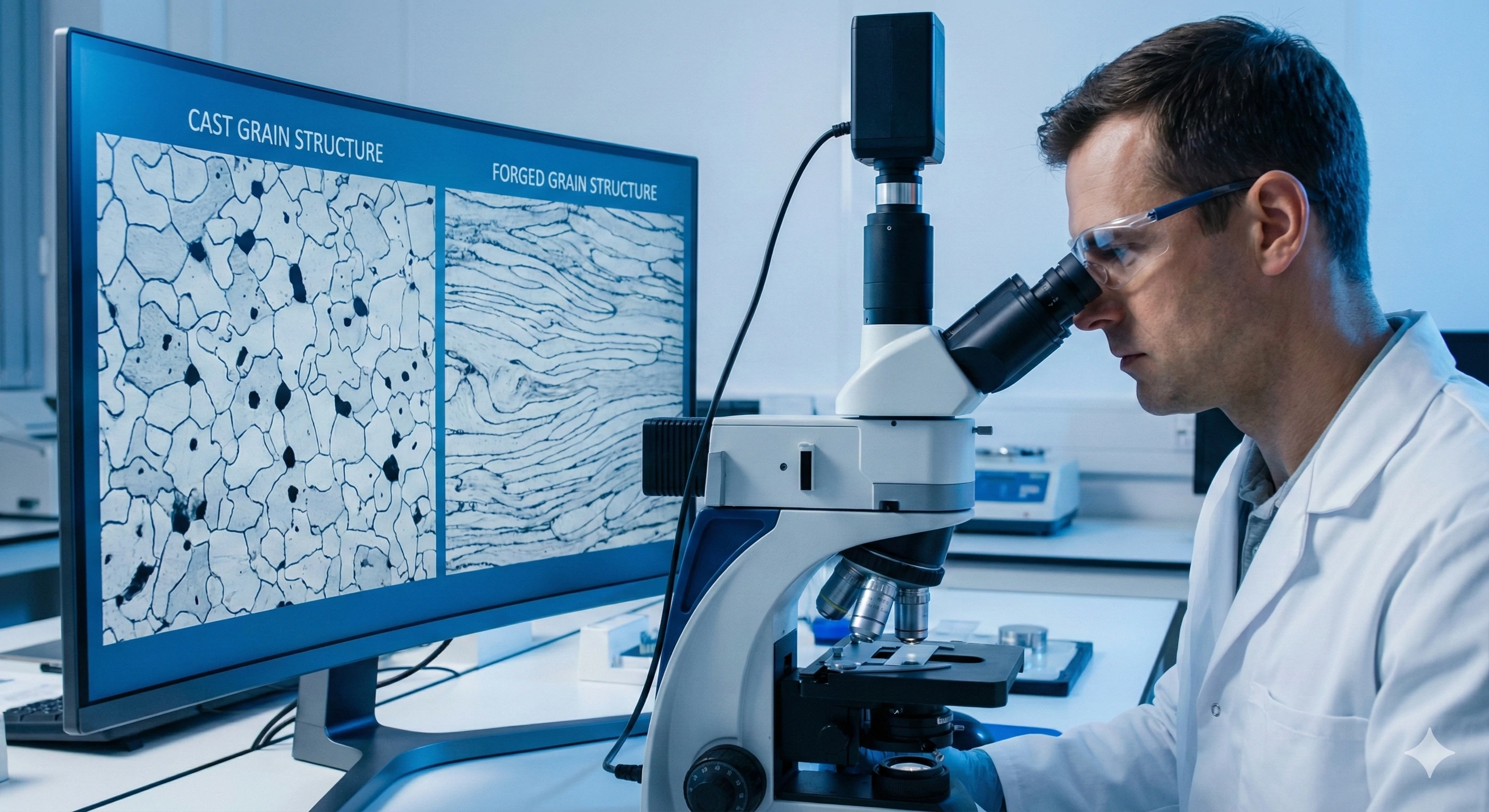

When our quality control team sends a part to the lab for microscopic analysis, they are looking at the "grain." This is the invisible differentiator that you cannot see with the naked eye, but it determines how long a product will last under stress. Understanding is the most scientific way to distinguish between a casting and a forging.

Casting produces a random grain structure where grains grow equally in all directions as the metal cools, offering uniform strength. In contrast, forging creates a directional, aligned grain structure that flows with the shape of the part, providing superior fatigue resistance.

The River Analogy

Imagine a river flowing around a bend. The water flows smoothly in the direction of the channel.

-

Forged Grain: Like the river, the grain follows the contour of the part. If you forge a hook, the metal grains bend around the curve of the hook. This continuous flow gives the part incredible resistance to snapping.

-

Cast Grain: Imagine a pile of sand. The grains are stacked randomly. There is no specific direction. This means the part has —it is equally strong (or weak) in all directions.

Why Does This Matter?

For static parts, like a glass clamp holding a panel in place, the random grain structure of casting is perfectly adequate and safe. The loads are constant and predictable. However, for parts that face —like a car axle that spins millions of times—the aligned grain of a forging stops cracks from spreading.

Grain Structure Comparison

| Feature | Casting (Foundry) | Forging (Forge) |

|---|---|---|

| Grain Orientation | Random / Isotropic | Directional / Anisotropic |

| Internal Integrity | Possibility of porosity (air pockets) | High density, voids closed by pressure |

| Impact Resistance | Lower | Very High |

| Fatigue Life | Standard | Extended |

Why You Can't Forge Everything (The Limit)?

We often advise clients who demand "forged only" products that their design might make forging physically impossible. While forging offers superior strength, it is a restrictive process. There is a reason why foundries like ours exist and thrive: we can make things that a hammer simply cannot.

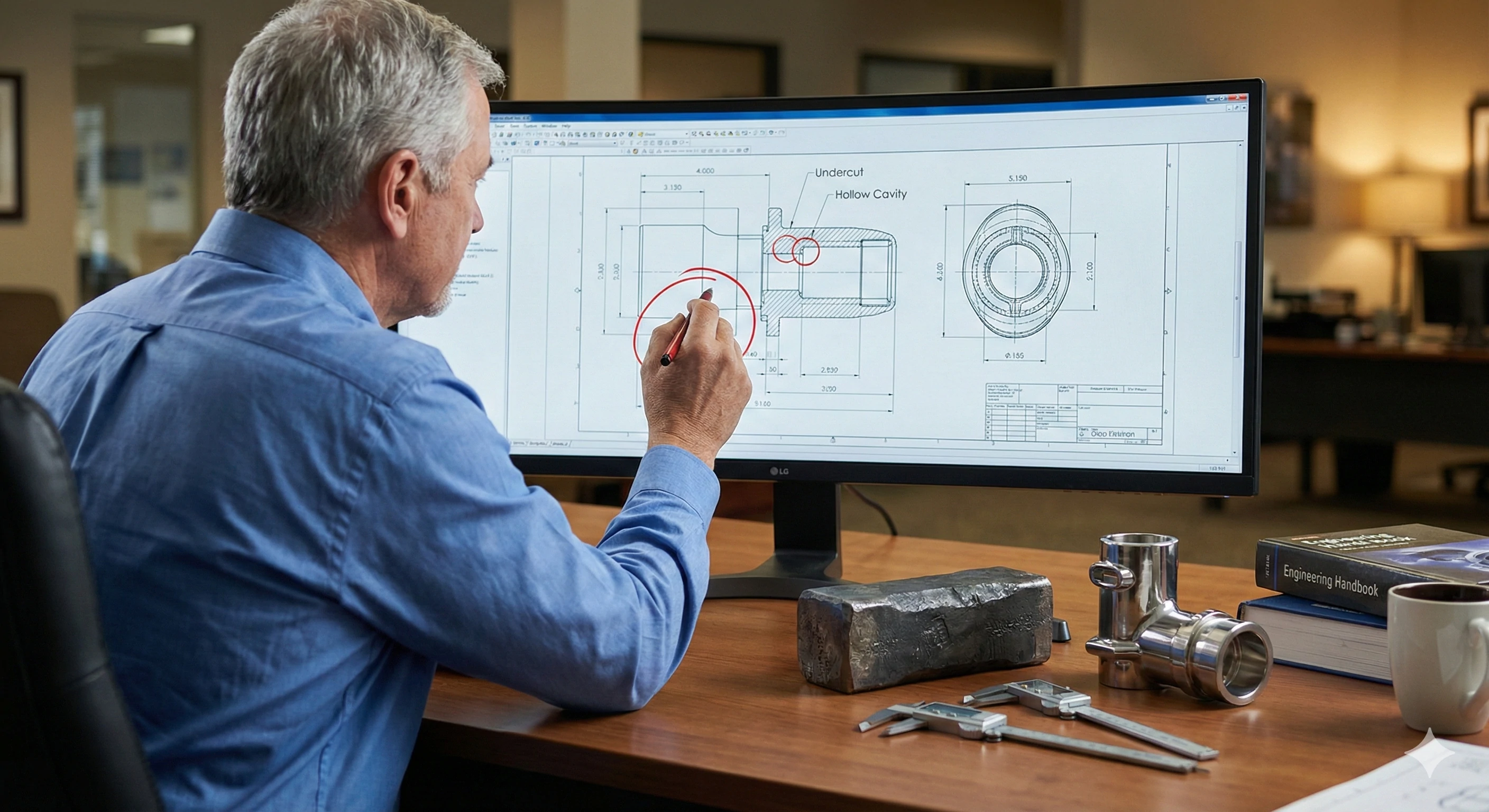

Forging is limited by geometry and material properties; you cannot forge parts with complex internal hollows, undercuts, or intricate ribs. Additionally, brittle materials like certain cast irons or superalloys will crack under the impact of a hammer and must be cast.

Limitation 1: The Shape (Geometry)

A forge works by sandwiching metal between two dies. If your part has an "undercut"—a feature that would lock the part inside the die—you cannot forge it.

-

Hollow Parts: You cannot forge a complex hollow sphere or a valve body with twisting internal passages. The solid slug cannot magically become hollow without expensive machining later. Casting creates these hollows naturally using cores.

-

Intricate Detail: Forging struggles with sharp corners and thin, standing ribs. The metal cools too fast to fill .

Limitation 2: The Size

Casting has an incredible size range. We can cast a tiny 10-gram jewelry ring, or a shipyard can cast a 100-ton anchor in a massive sand pit. Forging massive parts requires presses the size of buildings, which are rare and incredibly expensive.

Limitation 3: The Material

Not all metals like to be hit.

-

High Carbon Cast Iron: If you hit it with a hammer, it shatters like glass. It must be cast.

-

Complex Alloys: Some used in jet engines are too tough to deform plastically. They must be vacuum cast.

Cast vs. Forged: Which Should You Choose?

When we review a client's CAD drawing, we look for specific features that dictate the manufacturing path. If the design features a sleek, modern glass railing clamp with specific locking mechanisms, we almost always steer toward investment casting. However, if the client needs a high-tension bolt, we point them toward a forge.

Choose forging for simple shapes that require extreme toughness and impact resistance, such as tools or axles. Choose casting for complex geometries, hollow parts, or when you need a near-net-shape component to minimize expensive machining costs.

The Decision Matrix

To help you decide, we have compiled this comprehensive matrix based on our years of manufacturing experience.

| Factor | Choose Foundry (Casting) If... | Choose Forge (Forging) If... |

|---|---|---|

| Part Geometry | Complex, hollow, undercuts, thin walls. | Simple, blocky, round, solid. |

| Primary Stress | Compressive or static loads (e.g., holding glass). | Impact, shear, or cyclic loads (e.g., engine parts). |

| Tolerance | Excellent (Investment Casting is very precise). | Good, but often requires more machining. |

| Material | Brittle metals or complex alloys. | (Steel, Aluminum, Titanium). |

| Cost (Small Run) | Lower tooling costs generally. | High tooling costs (Dies are expensive). |

| Cost (High Vol) | Competitive. | Very economical for millions of simple parts. |

Real-World Examples

-

Glass Spigots: These are almost always Cast. The shape includes a base plate, a clamp body, and screw holes. Forging this would require massive machining to remove material, wasting money.

-

Door Hinges: Cast. The interlocking knuckles of a hinge are difficult to forge precisely.

-

Wrenches & Hammers: Forged. If you drop a cast hammer, it might crack. A forged hammer is practically indestructible.

Conclusion

The debate between foundry and forge is not about which process is "better"—it is about which process is right for your specific part. Forging shapes the metal; casting creates the metal. If your project requires the intricate elegance of a stainless steel glass railing system, casting provides the geometric freedom you need. If you are building an engine that needs to survive millions of explosions, forging provides the necessary grain structure.

At Aleader, we understand the nuances of these processes. Whether you are sourcing glass hardware or custom components, knowing the difference ensures you get the quality you pay for.

Does your project require complex geometries that forging can't handle? We are a precision Investment Casting Foundry specializing in high-strength Stainless Steel components. Contact us for a feasibility review.

Common Questions About Casting and Forging?

Is forged steel better than cast steel?

"Better" is a relative term. Forged steel is certainly stronger and tougher against impact because of the aligned grain structure. However, cast steel is "better" for design flexibility, allowing engineers to create shapes that are physically impossible to forge.

Can a factory be both a foundry and a forge?

It is rare. The equipment required is totally different. A foundry needs furnaces, crucibles, and shell-making robots. A forge needs massive pneumatic hammers and induction heaters. Most companies specialize in one or the other to maintain quality.

Are valves cast or forged?

This depends on the size and pressure rating. Small, high-pressure valves (under 2 inches) are often forged for maximum strength. Large valves (over 2 inches) or valves with complex internal flow paths are almost always cast because forging them is too difficult or expensive.

Footnotes

1. Comprehensive overview of the investment casting manufacturing process.

2. Definition and characteristics of metal billets used in forging.

3. Explanation of dies used in various metal shaping processes.

4. Technical causes and prevention of gas porosity defects.

5. Scientific explanation of crystal grain growth in materials.

6. Definition of materials with identical properties in all directions.

7. Understanding material fatigue under repeated fluctuating stresses.

8. Industry overview of metal casting design capabilities.

9. Research on high-performance alloys for aerospace applications.